\(\phi = 1.618...\). Much like \(\pi\), \(\phi\) shows up in the most unexpected places.

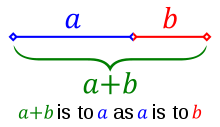

Where does \(\phi\) come from? One way to find \(\phi\) is to ask a simple question about line segments. If I had a line with a single point on it, at what point does the ratio of the entire line to the larger segment equal the ratio of the larger segment to the smaller segment?

If we say that the larger segment has length \(a\) and the smaller segment has length \(b\), then we could express this as an equation. Before we do, let’s use some examples to prove to ourselves using intuition that this point actually exists. What if \(a = b\)? Then the ratio of the entire line to \(a\) would be \(\frac{2}{1}\), and the ratio of \(a\) to \(b\) is \(\frac{1}{1}\). What if \(a\) was twice as big as \(b\)? The ratio of the entire line (\(a+b\)) to \(a\) would be \(\frac{3}{2}\) and \(a\) to \(b\) would be \(\frac{2}{1}\). In the first example, \(2 > 1\) and in the second \(1.5 < 2\). Since moving the point that separates the line into \(a\) and \(b\) is a continuous function, we know that there must be a point that the two values are equal!

In fact, we can use the equation

\[\frac{a + b}{a} = \frac{a}{b}\]as this is exactly what we are trying to find. Also since we’re looking at a ratio, we can set one of the numbers \(a\) or \(b\) to whatever we want and solve for the other one. For convenience let’s use \(a = 1\), although it really doesn’t matter (you can prove this to yourself by trying to substitute any number for either \(a\) or \(b\)). We now have

\[1 + b = \frac{1}{b}\]Since we’re solving for \(b\), let’s use the variable \(x\) instead and rearrange to a more familiar quadratic expression

\[x + x^2 = 1\]To solve this, let’s plug it into the quadratic formula

\[x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a}\]with \(a = 1, b=1, c=-1\). This gives us the solution that \(x = \frac{\pm \sqrt{5} -1}{2}\). Since we’re talking about lengths, \(x = \frac{-\sqrt{5} - 1}{2}\) doesn’t make sense because it is less than zero, so we are left with the solution \(x= \frac{\sqrt{5} - 1}{2}\). Low and behold \(\frac{\sqrt{5} - 1}{2} = 0.618... = b\). This means that the length of the total line is \(a + b = 1 + 0.618... = 1.618...\) and the ratio is \(1.618... : 1\).

At this point you may be asking, why am I spending so much time talking about this number? What is beautiful about it?

The ratio \(1 : 1.618...\) is often called the golden ratio and appears everywhere.

The video above starts with the fibonacci numbers and is directly related to a previous post of mine where I explore how to generate fibonacci numbers.

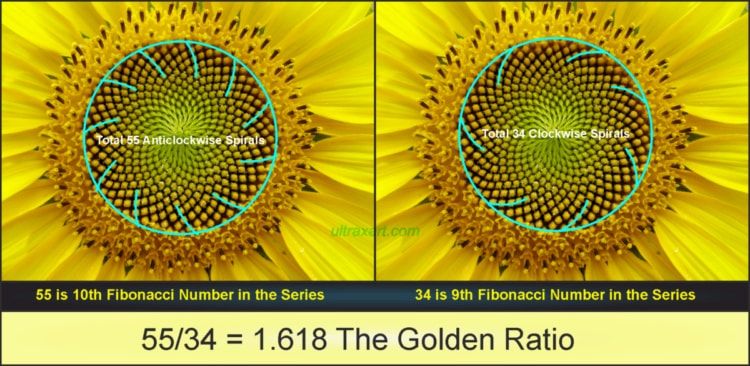

The second main idea that the video explores is how the angle 137.5 degrees is used in nature. 137.5 degree is what you get when you divide 360 degrees into two segments that are related by the golden ratio. But why the golden ratio? Why not a normal ratio that can be expressed as a fraction?

The example given in the video is the distribution of sunflower seeds, but this also applies to where new branches sprout from previous branches. For the sunflower seeds, they are created in the center and then have to be pushed outward. What should they be pushed? Our intuition says that they should go where they would have the most room, where the least seeds currently are. To see why the golden angle is the perfect new angle for each new seed, let’s think about what would happen for other angles.

Let’s say that the sunflower decided to spit out seeds every 180 degrees. The first two seeds would be perfectly situated, but after that they would be pushed exactly where previous seeds are. We could concoct a different angle, but as long as it is a fraction of whole numbers \(\frac{X}{Y}\), we could start overlapping again after at most \(Y\) times. This is why nature doesn’t use clean fractions, it uses irrational numbers. Irrational numbers are exactly the numbers that cannot be expressed as a fraction of two whole numbers. But again we have to ask ourselves, why \(\phi\)?

\(\phi\) is actually the most irrational number. What does that even mean? So every irrational number can be expressed as the sum of an infinite sequence. You can use the term “more irrational” to express sequences that take longer to converge on their infinite sum. \(\phi\) is actually proven to be the slowest at converging in a theorem by Hurwitz. How do we generate \(\phi\)? The fibonacci numbers are one way, but it can also be expressed in it’s continued fraction expansion as

\[1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + ...}}}}}}\]Therefore nature uses the most irrational number to ensure that branches and sunflower seeds get put in the most optimal position. This also explains why fibonacci numbers show up everywhere in nature. The fibonacci numbers are the best whole number approximations for the golden ratio, and since items in nature can’t have fractional values, they instead take on fibonacci numbers.

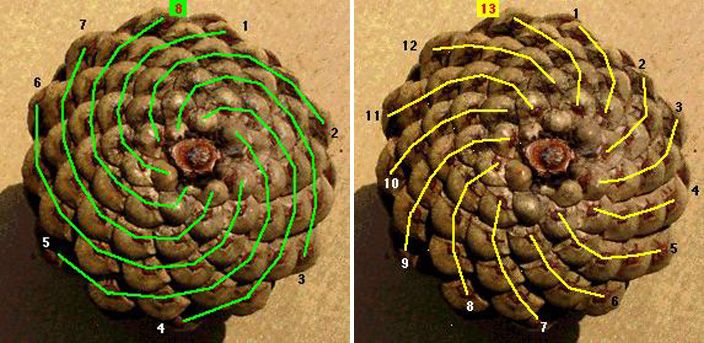

If you take a pineapple or pinecone and count the number of spirals on it, there will be a fibonacci number of spirals.

Look at any flower: petals arranged in fibonacci spirals. The cool thing is that there are often many different ways to count the spirals on one of these objects: each of the spirals will be a fibonacci number!

Numberphile has a video on this very subject, if you are interested in seeing more of the math behind \(\phi\).